How Pro Sports Teams Have Become Big Players In Commercial Real Estate

Welcome to Part 3 in our series on stadium anchored mixed-use development, a concept that is changing professional sports, commercial real estate and the cities, towns, neighborhoods and even states where professional sports stadiums and arenas are located.

In Part 1, we discussed the aspirations of the NFL’s Chicago Bears to build a new, state of the art multi-purpose stadium and adjacent mixed-use development on the former site of a Chicago-area horse racing track, an ambitious plan emblematic of the surging sports anchored development trend.

In Part 2, we looked at the business side of professional spectator sports, a massive, $179 billion industry, as well as the new stadium construction boom that kicked off in the late 1990s and shows no signs of halting.

In this installment, we discuss the modern history of sports stadiums in the US and the evolution of stadium revenue and financing models.

A Brief History of US Sports Stadiums

Sports Stadiums, Pre-World War II

Pre-World War II, most sports stadiums were built by the teams themselves using private funds and were site-driven, designed to fit into the urban neighborhoods where they were located, both physically and architecturally1.

Venerable old ballparks like Wrigley Field and old Comiskey Park in Chicago, Yankee Stadium and the Polo Grounds in New York and Fenway Park in Boston are prime, familiar examples.

Relatively few people owned automobiles then—people living in and near cities relied heavily upon public transportation– so there was no need to surround stadiums with parking.

Very few sports stadiums at the time were publicly funded or municipally owned. Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, constructed in 1923 and still standing and in use today, was the first sports venue that was built using any public funds2.

Sports Stadiums, Post World War II

After World War II, professional sports, sports stadiums and stadium financing and ownership all began to change. As the country began to heal from the war, the popularity of professional sports skyrocketed and sports became a lucrative business.

Eventually, as teams’ local fanbases grew, their stadiums became local economic engines on gameday and the teams generated substantial tax revenues for the cities and states they called home.

The Dawn of Publicly Funded Sports Stadiums

Recognizing their growing clout, team owners began demanding new stadiums paid for with public funds to draw more fans, increase revenue and boost their bottom line, threatening to relocate their franchises elsewhere if local government didn’t acquiesce.

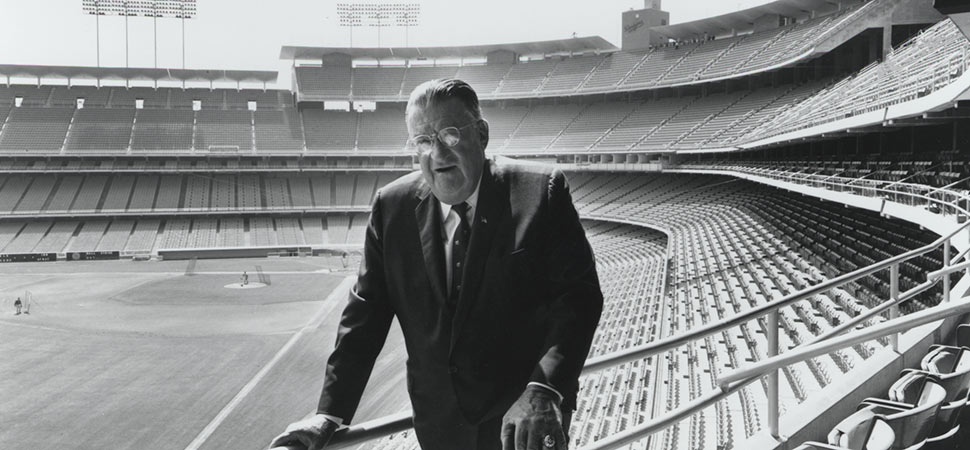

The Brooklyn Dodgers and then team owner Walter O’Malley were the first to make good on their threats, relocating to sunny Los Angeles, California in 19583 after New York City officials repeatedly rebuffed their requests for a new, publicly funded stadium.

The Dodgers’ cross-town rivals, the New York Giants, simultaneously followed suit, moving to San Francisco in 19584 after the foggy northern California city lured them with promises of a new, taxpayer funded stadium.

Soon thereafter, not wanting to lose their professional sports teams– angering fans, alienating voters and losing a valuable source of tax revenue and civic pride in the process– cities and states began bowing to team owners’ wishes, building new stadiums using taxpayer funds. From roughly the mid-50s through the mid-70s, approximately 75% of new stadium costs were paid for with public funds5.

The Multi-Purpose Stadium Era

The 1960s ushered in the era of the multi-purpose stadium, stadiums that were designed and built to accommodate multiple sports6, most commonly baseball and football.

Among the more high-profile were the Houston Astrodome, former home to MLB’s Astros and the NFL’s Oilers, built in 19657; Philadelphia’s Veterans Stadium, which opened in 1971 and hosted both Eagles football and Phillies baseball games8; and Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium, the former home of both MLB’s Pirates and the NFL’s Steelers, which opened in 19709.

The Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome in Minneapolis, which opened in 1982, was the very epitome of a multi-use sports stadium. The NFL’s Vikings, MLB’s Twins, NBA’s Timberwolves and University of Minnesota Golden Gophers football team all called the Metrodome home at various points, and the venerable stadium with the inflatable roof hosted two NCAA Men’s Basketball Final Four tournaments and many other high-profile sporting events10.

Multi-Purpose Stadium Similarities

Besides hosting sporting events and concerts, the multi-purpose stadiums had several things in common:

- Aesthetically, most were drab and monolithic, constructed of cold steel and concrete, with few memorable architectural features. Function— providing seats, concessions and restrooms for as many paying, revenue-generating fans as was practical and getting those fans in and out of the stadium efficiently—was heavily prioritized over form.

- Most new stadiums at the time were surrounded by a sea of surface parking lots to accommodate fans. By that point, most fans were driving to games versus taking public transportation, a result of the mass migration to the suburbs from cities, a social trend that had profound and far-reaching consequences for big cities and their residents, businesses, finances and commercial real estate.

- In addition, unlike stadiums of old, which were located in the heart of bustling urban neighborhoods, most new sports stadiums built during the 1960s and 70s were located in sparsely populated or economically disadvantaged areas or the suburbs, where land was relatively cheap and plentiful and the presence of a stadium wouldn’t interfere much with daily life.

Sports Stadiums and Eminent Domain

Sometimes, cooperative state and local governmental officials would exercise their powers of eminent domain11 and essentially force the landlords, residents and businesses in the neighborhood to sell their properties to make way for the new stadium, which they argued would benefit the public by creating jobs and increasing tax revenue.

Public Funds For Stadiums

Perhaps the most consequential similarity between the multi-use stadiums: as mentioned, they were largely paid for by taxpayers, as was the next generation of sports stadiums and arenas.

According to a 2010 study from the National Conference of State Legislatures, 22 stadiums built since the 1960s were financed entirely with public funds, most commonly with tax-free municipal bonds12.

Between 1991 and 2010, 101 new sports stadiums were built, most at least partially funded by taxpayers13.

Similar to eminent domain, team owners and local politicians argued that a new sports stadium or arena would be an economic engine for the neighborhood, city and state—even the region—essentially paying for itself and then some by generating new jobs and millions in additional tax revenue, while spurring additional development in the surrounding area, which in turn would create even more jobs and more tax revenue.

And, much like Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley back in the late 1950s, team owners would threaten to relocate their pro sports franchise if they didn’t get their way, which led to some owners getting sweetheart stadium deals funded completely by taxpayers.

The Chicago White Sox New Stadium Saga

Major League Baseball’s Chicago White Sox had played their home games in Comiskey Park, on the city’s south side, since it opened its gates to fans in 191014.

After buying the team from legendary baseball impresario Bill Veeck Jr. in 1981, new owners Jerry Reinsdorf and Eddie Einhorn began lobbying Chicago and Illinois state officials for a new publicly financed stadium.

When a deal in Chicago wasn’t forthcoming, Reinsdorf and Einhorn looked to Addision, IL, a suburb about 25 miles west of Chicago.

After Addison voters narrowly rejected a proposal to finance a new stadium for the White Sox, the team’s owners played hardball, threatening to move the White Sox to St. Petersburg, FL to play in the then under-construction and completely publicly-funded Florida Suncoast Dome – now Tropicana Field– unless the City of Chicago and State of Illinois came through with a new stadium deal.

In 1988, The Illinois General Assembly finally passed a bill approving public funds for a new stadium just minutes before the team’s final deadline15.

The Illinois Sports Facilities Authority, a governmental body created specifically to oversee the funding and operation of the White Sox new stadium, used its powers of eminent domain to acquire about 100 acres of property adjacent to old Comiskey Park16.

Construction of the new stadium– which would also be named Comiskey Park initially, and which local fans would refer to as “New Comiskey Park” to avoid confusion—was funded entirely through municipal bonds and a hotel tax. The White Sox contributed no monies17.

Even after construction of their new stadium was well underway, the team continued to wield the threat of relocation to negotiate one-sided lease terms, to the point where the White Sox paid zero rent the first 18 years and their stadium rent was among the lowest in MLB thereafter18.

The Traditional Stadium Revenue Model

As far as that additional neighborhood development around new stadiums, teams were, for the most part, hands off. The prevailing sports business model for decades was to generate stadium revenue on game days through traditional streams: ticket sales, parking, concessions, souvenirs and in-stadium advertising, including signage on scoreboards and in concourses.

Concerts, ice shows, circuses, festivals and other non-sports events held at the stadium were also a source of revenue for teams.

However, most sports stadiums and arenas are used only a small fraction of the year. For example, between the preseason and regular season, each NFL team plays 10 home games. Economist Victor Matheson found that between 2000 and 2009, the average NFL stadium hosted 4.9 non-league events a year19. That means the average NFL stadium is in use only 15 days a year and sits idle the other 350, nearly 96% of the calendar year.

While teams in North America’s other four major leagues play more regular season home games– 81 for MLB teams, 41 for NBA and NHL teams and 17 for MLS teams —their stadiums are empty and quiet most days too, even including preseason games, the playoffs—if the team makes the post-season—and special events.

On days no events are scheduled— the vast majority– stadiums and arenas generate zero revenue for their home teams. No tickets are sold; the acres of surrounding parking lots sit empty. There are no fans to buy concessions or bobbleheads or game programs. The teams recognized this.

Changing Public Sentiment About Stadiums

Around the same time pro sports teams started reconsidering their traditional stadium revenue models, something else occurred, something pro sports teams, with all their power, influence, connections and money couldn’t control: taxpayers and politicians were becoming increasingly resistant to the idea of using public funds to finance new stadiums for private businesses owned by extremely wealthy individuals and big, deep-pocketed corporations20.

This deepening public sentiment was driven by two main factors: state and municipal operating budgets had been tightening for years, to the point where funds for critical services, like education, infrastructure upkeep and police and fire protection, were being cut21; and that new sports stadiums and arenas were hardly the economic catalysts team owners had claimed22, with study after study showing that team owners profited greatly from the stadium deals, but the cities, states and taxpayers that financed their venues did not.

In 2017, 83% of economists surveyed agreed that for taxpayers, the cost of subsidizing a new stadium is likely to outweigh the local economic benefits23. Similarly, economics professors Roger Noll and Andrew Zimbalist conducted a comprehensive review of public stadium investment and in every case found that a new sports venue had a small or even negative impact on economic activity and employment24. Sports economist Michael Leeds suggests that a professional baseball team has about the same economic impact on an area as a midsized department store25.

Pro Sports Reaches A Crossroad

Consequently, professional sports teams found themselves at a critical crossroads. Under increasing financial and public pressure, they began looking for new ways to finance new stadiums and to increase revenue from those stadiums.

Eventually, they turned their attention to one of the promised but mostly unrealized benefits of new stadiums they had largely ignored previously: redevelopment of the area around the stadium and the shower of economic benefits that would bring.

Next, Pro Sports Teams Get Off The Sidelines and Join The Commercial Real Estate Game

In the next post in our series on stadium anchored mixed-use development, we’ll discuss why and how professional sports teams embraced commercial real estate, adapted their revenue models and became major commercial real estate developers and owners.

On a related note, if you happen to be involved in sports anchored development, Realogic offers several services and solutions that can help you maximize the returns on your next project:

- Our off-the-shelf Excel development models have been tested and refined over the course of 30 years and thousands of successful and profitable commercial real estate projects and can be used to accurately model even the biggest and most complex mixed-use projects. Using Realogic’s accurate, proven models instead of taking on the formidable task of building your own will save you time and money, eliminate the trial and error and give you greater confidence in your numbers.

- Or, if you’d prefer, we can do the financial modeling for you. Realogic’s skilled, experienced consulting team has modeled thousands of commercial real estate projects of all types and complexity over the past 30 years, including ground-up development and mixed-use properties. We work quickly and accurately and can work in your choice of modeling platform. Another big benefit: our transparent financial models feature exposed formulas so you can see exactly how numbers were calculated and make modifications and adjustments as you see fit.

- Finally, if your sports anchored project is located in a Qualified Opportunity Zone, as many are, we have extensive experience working with QOZs and QOFs. We know how to deftly navigate the ins and outs of Opportunity Zones and offer a variety of expert services and solutions to help you maximize the return on your Opportunity Zone investments.

About The Author

Terry Banike is Vice President of Marketing for Realogic. Over the course of his career, he has worked in marketing, communications, journalism and public relations, and has written news stories and features for newspapers, trade publications, newsletters and blogs. A rabid reader of anything and everything on commercial real estate, Terry closely follows commercial real estate news and trends and frequently posts about real estate on the Realogic Blog. He can be reached at tbanike@realogicinc.com.